-

BIO

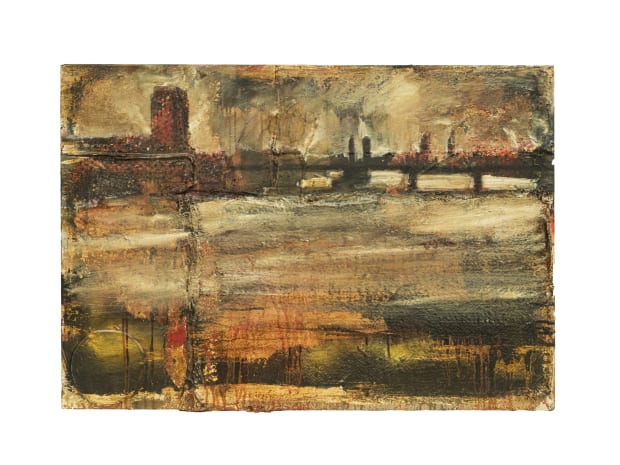

Born in Canada in 1946, Dale Inglis graduated from art school in Canada and Byam School of Art in London, before settling in England, with his family, in 1979. Working with a group of artists in Metropolitan Wharf, on the banks of the River Thames, amongst the derelict warehouses of London's Docklands, and later from his studio at Pullens Yards in Walworth, South London and his home in Sussex, Dale Inglis' fascination for the Thames and its bridges has endured for over 40 years. The scene where the river flows under Cannon Railway Bridge has become a recurring motif in his unique body of work.

One of his chief interests has been the study and depiction of the River Thames. "It came about originally a long time ago, when I first came to London, and I found myself with a studio that overlooked the Thames," says Inglis. "I was there for a while, and I started painting what was outside the window, and then I extended my range up and down that particular section of the Thames. At that time, it was all, mostly, decaying warehouses and much of it was corrugated iron and that sort of thing."

He experienced, daily, the river's grandeur, its history and changing appearance and, not least, the sense of continuity it implied. Some of his paintings are small, others are huge and often made of multiple panels, with a repeating motif reflecting a concern for issues of memory and time. The works suggest endlessly repeated journeys and endlessly repeated tides, offering glimpses of a shifting and elusive reality, rather than simply depicting an accurate representation of place.

Displaying a singular technical ingenuity, Dale Inglis has developed a unique and highly distinctive approach which involves building up his surfaces with a wide range of materials which include varnish, opaque paint, decorator’s paint, salvaged and recycled drawings and sketches from life, fabrics and pages torn from books.

Once finished and dried, the surfaces are then subjected to a process of destruction using paint remover, heat gun, blow torch, scrapers and sandpaper - a process that causes the paint to bubble, curl and shrivel, revealing a palimpsest with tantalising fragments of image and meaning. This surface may be modified further, or it may need to be built up again, and so the process of experiment and improvisation continues until a final image is nurtured into life.

It is in this slow, patient and painstaking way that Dale Inglis’s paintings evolve; some taking more than a year. He also has a large number of boards on the go at the same time, leaving them to reveal themselves between the spells of physical working. They may stem from landscape experience and contain landscape references, but they are squarely in the mainstream of modernist abstract practice, with roots in the work of Turner, Rothko and Tapies.

In this way, Dale Inglis finds a meeting of the external world and his own inner experiences, where the underlying feeling is for what the poet T.S. Eliot has referred to as 'the timeless moment'.

-

ARTIST STATEMENT

My paintings represent an ongoing fascination with bridges and riverscapes.

Each panel has an earlier life history, which informs the preliminary stages in the development of the work, but ultimately may almost entirely be submerged. There is no 'tabula rasa'.

The unfolding of the process then involves painting and repainting versions of essentially the same image, alternating with layers of varnish, opaque paint, irregular dot patterns and text, created using decorator’s paint, oil colour, varnish, aerosol and biro. This can take months or sometimes years as each layer is allowed to dry and cure. The top layer is opaque white.

The paintings are then subjected to a process of deconstruction, brought about by the use of paint remover, heat gun, blow torch, scraper and sandpaper. The layers of paint bubble, curl, shrivel and go up in smoke. The work proceeds in stages, combining both intentional strategies and chance.

Sometimes the destruction is nearly total and the process of building begins again. The result is a rich surface bordering on the abstract, a palimpsest with tantalising fragments of meaning that nonetheless embody a truth about the subject matter, the painting process and the past. The painter has become an archaeologist. Each layer is fashioned as if it were intended to be a finished piece in its own right. It also allows for experimentation and improvisation and the adoption of alternative painting personas. No record is kept of successive intermediate layers.

Working on many paintings at the same time, as well as the protracted time scale involved, ensures that each uncovering is a voyage of discovery. It’s also a bit like seeing your life passing in a flash. It can be exciting but nerve-wracking. The inclusion of several panels in a single work can be seen as a parallel to cinema. It involves endlessly repeated journeys, coming and going, and endlessly repeated tides, offering glimpses of a shifting and elusive reality.

It is also intended that references to particular light or atmospheric conditions be overridden by a deeper truth based on elemental colour, a radiant and vibrant surface and simple abstract divisions.

Some of the titles are from T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, in which Eliot returns again and again to the themes of cyclical history, referencing events and people which are the same and not the same.

In the poem he describes a form of historical and personal erosion through which distinct attributes are blurred and reduced in the passage of time, but which also accrete and accumulate over years or centuries to create a larger truth.

DALE INGLIS

-

A NOTE ABOUT COLOUR

Among the ways that the work has evolved over a number of years is the use of colour. Earlier work is based on the primary colours (red, yellow and blue), frequently unmixed and applied more or less mechanically. Later work is based on the much older palette of black, white, red and yellow. The absence of blue implies the absence of green. These pigments are derived from clay, chalk and charcoal. Evolution has hard-wired these four colours into the human subconscious.

They have been fundamental to painting since the beginning of time. The thread runs from Palaeolithic artists through the ancient Egyptians and Greeks, mediaeval painters, the masters of the Renaissance, Frans Hals, Rembrandt, Courbet, Anders Zorn (after whom the palette is sometimes named), Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Alberto Burri and Anselm Kiefer.

Carl Jung believed the four colours were part of the collective unconscious. His thinking was informed by his study of alchemy and its tendency to understand the world in terms of groups of four (quaternities).

The four colours remained fundamental and sacred from ancient times to at least the Renaissance and beyond. It wasn’t the absence of the availability of blue and green, but the fact that red, yellow, black and white were part of a vast complex of related ideas that are part magic, part myth, part folklore and part science, with religious, mathematical, musical and cosmological connotations.

I tend to follow the mediaeval practice of using the colours unmixed to avoid sapping them of their purity and power.

DALE INGLIS